A few afternoons ago, gunshots woke me from an intentionally meditative state. Only they weren’t gunshots, as it took me a nanosecond to realize, but the sound of someone’s vehicle entering our building garage, driving over a tube-encased door control mechanism as it did so. I’ve lived here for several years now and the noise seldom bothers me, but it would if I lived over, below, or next to the garage. Fortunately, our building was designed and constructed such that no one does, and as a noise both air- and structure-borne, that unsettling bang-bang would be truly nightmarish if anyone did.

In the last instalment of our continuous observations on noise issues in multi-family dwellings, I noted that strata corporations are legally bound, in accordance with Standard provincial Strata Bylaws, to address and mitigate unreasonable noise when it originates from common property.

Other key takeaways included the facts that:

- These Standard Bylaws, however, fail to define what constitutes unreasonable.

- Strata corporations are encouraged to customize, clarify, and enforce these Bylaws. But too often they don’t.

- Nuisance law presents an avenue to explore when Bylaws prove inapplicable. I’ll explore it further here.

Much of what can read as homeowner and strata group complacency may stem from a (perhaps sometimes unwarranted) trust in building codes.

Many developers do not address structure-borne noise issues quite simply because there is no regulative requirement to do so.

The Canadian Building Code, as well as the provincial and municipal codes based on it, relate only to the control of airborne sound transmission. However, noise disturbance can also be experienced through the transmission of “structure-borne” noise, which occurs when building fabric is excited by impacts such as items dropped on or dragged across hardwood flooring. In addition, mechanical or electrical equipment (pumps, air-handling equipment, transformers or elevators) can impart continuous vibration into the structure.

As noted in an earlier post, the Building Code contains no provision for controlling structure-borne noise, so it’s hardly surprising that many developers do not address these issues quite simply because there is no regulative requirement to do so.

I blame the pictures. This one links to a recipe.

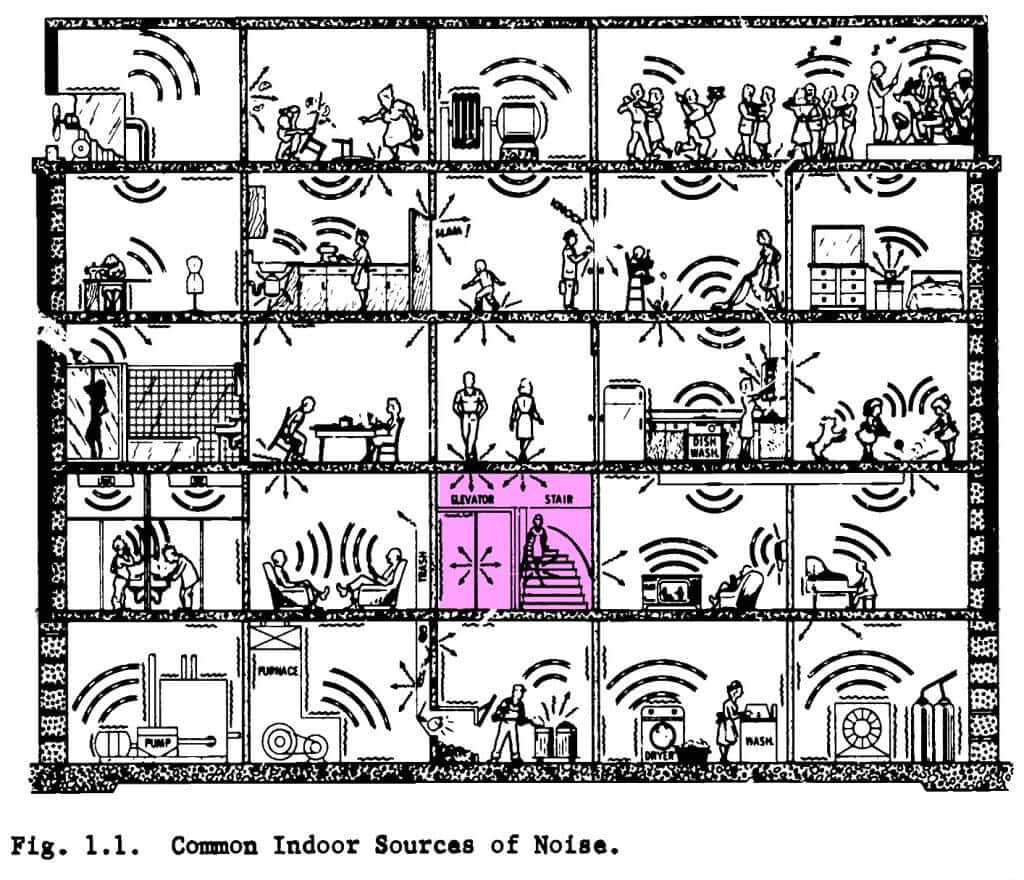

From A Guide to Airborne, Impact, & Structure Borne Noise Control in Multifamily Dwellings, published in 1967 by the US Dept. of Housing & Urban Development. Available as a free e-book, this work offers an interesting historical perspective. Spot the common property.

In the dated but still woefully relevant US government publication A Guide to Airborne, Impact, & Structure Borne Noise Control in Multifamily Dwellings, writers state:

Surprisingly, the frequency of complaints appears to be independent of income bracket in virtually all types of apartment buildings, including high-rise as well as low-story garden-type apartments. Luxury, middle- and low-income apartments register approximately the same number of complaints because most of the buildings utilize the same type of wall and floor assemblies. This fact clearly demonstrates that builders and architects do not consider privacy and quiet surroundings as necessities, much less luxuries.

The causes of most noise problems in multifamily dwellings originate in the early design stages of the buildings because of […] lack of concern about noise problems and […] failure to foresee where and under what circumstances noise might be a problem. (Emphasis mine.)

Most people will agree that what pleases one’s senses enhances one’s comfort. Oddly enough, a peaceful and relaxing environment apparently is not recognized as essential to comfort, judging from the fact that it is lacking in a high percentage of buildings. Obviously, we are approaching the time when [the building industry] must pay adequate attention to acoustical problems.

Before buying an apartment, consider asking your realtor or developer about the acoustic design standards of the building and confirm that they go beyond minimum Code requirements. With any luck, you’ll never have to deal with nuisance of the noisy variety.

The process of researching nuisance law took me down a rabbit hole that looks something like this:

Nuisance law: It’s a piece of tort.

Practiced in the UK, Australia, Canada, and many other parts of the world, common law (aka case law) is a body of unwritten laws based on court-established legal precedents set via individual cases. It comes into play when existing laws fail to provide an adequate foundation for judicial decision making. In contrast, civil law is, by definition, official legislation stemming from established civil codes.

So, where and how does nuisance law fit in? Although it sounds like a tasty baked treat, tort plays a role across legal categories. A cornerstone of the Canadian legal system, tort law provides compensation for people who have been injured or whose property has been damaged by the wrongdoing of others. When someone’s misactions result in, for instance, serious bodily harm, the criminal justice system may employ tort law in seeking a fair ruling. A lesser offence may be seen as more nuisance than crime; hence, nuisance law. I know more about it now than I did a week ago, and in future articles will rely on the mnemonic device “Nuisance law: It’s a piece of tort.” to help me remember it.

When strata corporations fail to mitigate unreasonable noise situations, affected unit owners can, as alluded to in Part I, apply to the Civil Resolution Tribunal (CRT) for dispute resolution. As applicants make their way through the five-part CRT Process, they may consider engaging an acoustical consultant at any stage, ideally early on.

With the help of BAP Acoustics consultants, two Vancouver-based apartment owners recently won a dispute with their strata council, which had failed to maintain and repair elevator equipment. The elevator, and related mechanical room machinery, had caused what was ultimately deemed an unreasonable level of noise and vibration in their master bedroom. The owners’ claim, that the noise interfered with “quiet enjoyment of their strata lot”, was agreed valid by a senior-level Tribunal member, who ordered the respondents (i.e. strata corporation) to compensate the applicants in numerous ways.

In a lengthy document detailing how decisions were reached, the overseeing CRT member states “I find the BAP report persuasive, and I rely on it.” Summarized here as per the CRT document, the BAP Acoustics report included the conclusions that:

- The maximum elevator noise levels measured in the two bedrooms exceeded the recommended criteria in both sets of guidelines*.

- Noise levels experienced in the unit […] are subjectively approximately twice as loud as the recommended maximum when the ensuite door is closed, and three times as loud when the door is open.

- The maximum noise criterion level from elevator noise was over 30 in the unit […] bedroom, 30 in the living room, and 35 in other areas. The CMHC’s guidelines set a maximum elevator noise criterion objective of 20 in bedrooms and living rooms.

- It is reasonable to expect noise complaints may arise from the occupants of unit […], and that remedial measures can be implemented to reduce noise levels by using the best available techniques (i.e. vibration isolation of structure-borne noise sources).

- While it may be that the noise levels are typical of the [the manufacturer’s] elevator, comparing [previous] noise readings [to our test results] indicates that industry noise standards are exceeded.

- BAP agreed with [a previous engineer’s] findings are elevator motor and the brake contactors are the source of the noise transmitted into unit […], and that while the control room wall maybe acoustically week, the main issue results from structure-borne noise transmission.

- BAP agreed with [a previous engineer] that the controllers should be isolated from the concrete slab. BAP also said that the control room fan should be resiliently mounted if supported within the structural slab, to reduce fan noise transfer.

- While acoustic weaknesses in the control room wall identified by [a previous engineer] should be addressed to increase sound insulation, the wall weaknesses were not responsible for the elevator noise transmission, [and that] the elevator noise can only be remedied by decoupling the elevator controller from the supporting floor slab and walls.

BAP Acoustics has been called upon to provide expertise in numerous similar cases, and once again, it turns out that structure-borne noise—for which the Building Code makes no provisions—is the sleep-robbing culprit that needs remedial attention. Wherever and however unacceptable noises originates, we can help you win back peace and quiet.